Citizens have long been able to bring defamation suits over published works under state libel laws. But it wasn't until 1964, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement in a case involving an advertisement commenting on police in Montgomery, Alabama, that the Supreme Court said that a state's libel laws were subject to free speech protections of the First Amendment. In that landmark case, New York Times v. Sullivan, the Supreme Court recognized that libel laws could have a chilling effect on debate about public issues and established that a public official had to show actual malice to win a defamation case. In this March 7, 1960 photo, police and firefighters train fire hoses on a crowd of blacks in Montgomery, Ala., as they gathered at a church for a planned march to the state capitol. They authorities blocked them while an angry white crowd stoody by. (AP Photo/Horace Cort, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Defamation is a tort that encompasses false statements of fact that harm another’s reputation.

There are two basic categories of defamation: (1) libel and (2) slander. Libel generally refers to written defamation, while slander refers to oral defamation, though much spoken speech that has a written transcript also falls under the rubric of libel.

The First Amendment rights of free speech and free press often clash with the interests served by defamation law. The press exists in large part to report on issues of public concern. However, individuals possess a right not to be subjected to falsehoods that impugn their character. The clash between the two rights can lead to expensive litigation, million-dollar jury verdicts and negative public views of the press.

Defamatory comments might include false comments that a person committed a particular crime or engaged in certain sexual activities.

The hallmark of a defamation claim is reputational harm. Former United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart once wrote that the essence of a defamation claim is the right to protect one’s good name. He explained in Rosenblatt v. Baer (1966) that the tort of defamation “reflects no more than our basic concept of the essential dignity and worth of every human being — a concept at the root of any decent system of ordered liberty.”

However, defamation suits can threaten and test the vitality of First Amendment rights. If a person fears that she can be sued for defamation for publishing or uttering a statement, he or she may avoid uttering the expression – even if such speech should be protected by the First Amendment.

This “chilling effect” on speech is one reason why there has been a proliferation of so-called “Anti-SLAPP” suits to allow individuals a way to fight back against these baseless lawsuits that are designed to silence expression. Professors George Pring and Penelope Canaan famously referred to them as Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation or SLAPP suits.

Because of the chilling effect of defamation suits, Justices William O. Douglas, Hugo Black, and Arthur Goldberg argued for absolute protection at least for speech about matters of public concern or speech about public officials. The majority of the Court never went this far and instead attempted to balance or establish an accommodation between protecting reputations and ensuring “breathing space” for First Amendment freedoms. If the press could be punished for every error, a chilling effect would freeze publications on any controversial subject.

Before 1964, state law tort claims for defamation weighed more heavily in the legal balance than the constitutional right to freedom of speech or press protected by the First Amendment. Defamation, like many other common-law torts, was not subject to constitutional baselines.

In fact, the Supreme Court famously referred to libel in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942) as an unprotected category of speech, similar to obscenity or fighting words. Justice Frank Murphy wrote for a unanimous Court that “[t]here are certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which has never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem. These include the lewd and obscene, the profane, the libelous, and the insulting or ‘fighting’ words.”

American and English law had a storied tradition of treating libel as wholly without any free-speech protections. In fact, libel laws in England and the American colonies imposed criminal, rather than civil, penalties. People were convicted of seditious libel for speaking or writing against the King of England or colonial leaders. People could be prosecuted for blasphemous libel for criticizing the church.

Even truth was no defense to a libel prosecution. In fact, some commentators have used the phrase “the greater the truth, the greater the libel” to describe the state libel law. The famous trial of John Peter Zenger in 1735 showed the perils facing a printer with the audacity to criticize a government leader.

Zenger published articles critical of New York Governor William Cosby. Cosby had the publisher charged with seditious libel. Zenger’s defense attorney, Andrew Hamilton, persuaded the jury to engage in one of the first acts of jury nullification and ignore the principle that truth was no defense.

The Zenger case was more of an outlier than a trend. It did not usher in a new era of freedom. Instead, as historian Leonard Levy explained in his book Emergence of a Free Press (1985) that “the persistent notion of Colonial America as a society where freedom of expression was cherished is an hallucination which ignores history. … The American people simply did not believe or understand that freedom of thought and expression means equal freedom for the other person, especially the one with hated ideas.”

Even though the First Amendment was ratified as part of the Bill of Rights in 1791, a Federalist-dominated Congress then passed the Sedition Act of 1798, which was designed to silence political opposition in the form of those Democratic-Republicans who favored better American relations with France.

The draconian law prohibited “publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government … with intent to defame … or to bring them … into contempt or disrepute.” The law was used to silence political opposition.

Until the later half of the 20 th century, the law seemed to favor those suing for reputational harm. For most of the 20th century, a defendant could be civilly liable for defamation for publishing a defamatory statement about (or “of and concerning”) the plaintiff. A defamation defendant could be liable even if he or she expressed her defamatory comment as opinion. In many states, the statement was presumed false and the defendant had the burden of proving the truth of his or her statement. In essence, defamation was closer to the concept of strict liability than it was to negligence, or fault.

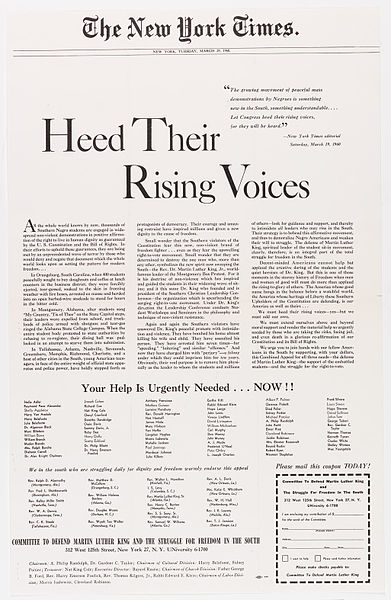

However, in the celebrated case of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the U.S. Supreme Court constitutionalized libel law. The case arose out of the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement. The New York Times published an editorial advertisement in 1960 titled “Heed Their Rising Voices” by the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King. The full-page ad detailed abuses suffered by Southern black students at the hands of the police, particularly the police in Montgomery, Alabama.

Two paragraphs in the advertisement contained factual errors. For example, the third paragraph read:

“In Montgomery, Alabama, after students sang ‘My Country, Tis of Thee’ on the State Capitol steps, their leaders were expelled from school, and truckloads of police armed with shotguns and teargas ringed the Alabama State College Campus. When the entire student body protested to state authorities by refusing to re-register, their dining hall was padlocked in an attempt to starve them into submission.”

In New York Times v. Sullivan, a city commissioner of Montgomery, Ala., sued the New York Times over a 1960 advertisement titled “Heed Their Rising Voices.” The ad highlighted struggles with police during the Civil Rights Movement. Because the ad contained factual errors, the libel claim could not be defeated by showing truth. The Supreme Court held that inaccurate statements in the ad did not negate the right to a free press and said to protect erroneous statements that are “inevitable in free debate” about public affairs, public officials must show actual malice before recovering damages. (Image of ad published March 29, 1960, public domain)

The paragraph contained undeniable errors. Nine students were expelled for demanding service at a lunch counter in the Montgomery County Courthouse, not for singing ‘My Country, ‘Tis of Thee’ on the state capitol steps. The police never padlocked the campus-dining hall. The police did not “ring” the college campus. In another paragraph, the ad stated that the police had arrested Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. seven times. King had been arrested four times.

Even though he was not mentioned by name in the article, L.B. Sullivan, the city commissioner in charge of the police department, sued the New York Times and four individual black clergymen who were listed as the officers of the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King.

Sullivan demanded a retraction from the Times, which was denied. The paper did print a retraction for Alabama Gov. John Patterson. After not receiving a retraction, Sullivan then sued the newspaper and the four clergymen for defamation in Alabama state court.

The trial judge submitted the case to the jury, charging them that the comments were “libelous per se” and not privileged. The judge instructed the jury that falsity and malice are presumed. He also said that the newspaper and the individual defendants could be held liable if the jury determined they had published the statements and that the statements were “of and concerning” Sullivan.

The all-white state jury awarded Sullivan $500,000. After this award was upheld by the Alabama appellate courts, The New York Times appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The high court reversed, finding that the “law applied by the Alabama courts is constitutionally deficient for failure to provide the safeguards for freedom of speech and of the press that are required by the First and Fourteenth Amendments in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct.”

For the first time, the Supreme Court ruled that “libel can claim no talismanic immunity from constitutional limitations,” but must “be measured by standards that satisfy the First Amendment.” In oft-cited language, Justice William Brennan wrote for the Court:

Thus, we consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.

The Court reasoned that “erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate” and that punishing critics of public officials for any factual errors would chill speech about matters of public interest. The high court also established what has come to be known as “the actual malice rule.” This means that public officials suing for libel must prove by clear and convincing evidence that the speaker made the false statement with “actual malice” — defined as “knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

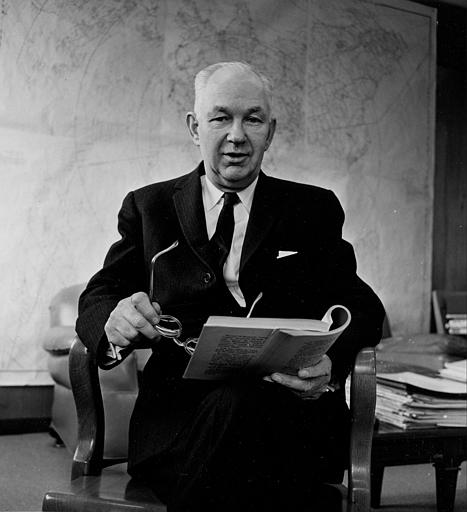

Wally Butts, the athletic director at the Univeristy of Georgia (and shown here in 1943 when he was coach) was accused in a magazine article of rigging a football game. His defamation case led to a extended rule by the the U.S. Supreme Court that public figures also had to meet the “actual malice” standard to win damages, although Butts himself won his case. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

The high court extended the rule for public official defamation plaintiffs in the consolidated cases of Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts and The Associated Press v. Walker (1967) .

The cases featured plaintiffs Wally Butts, former athletic director of the University of Georgia, and Edwin Walker, a former general who had been in command of the federal troops during the school desegregation event at Little Rock, Arkansas, in the 1950s.

Because the Georgia State Athletic Association, a private corporation, employed Butts, and Walker had retired from the armed forces at the time of their lawsuits, they were not considered public officials. The question before the Supreme Court was whether to extend the rule in Times v. Sullivan for public officials to public figures.

Five members of the Court extended the Times v. Sullivan rule in cases involving “public figures.”

Justice John Marshall Harlan II and three other justices would have applied a different standard and asked whether the defamation defendant had committed “highly unreasonable conduct constituting an extreme departure from the standards investigation and reporting ordinarily adhered to by responsible publishers.” The Court ultimately held that Butts and Walker were public figures.

However, sometimes the Court found that individuals were more private than public.

The Supreme Court clarified the limits of the “actual malice” standard and the difference between public and private figures in defamation cases in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974).

The case involved a well-known Chicago lawyer named Elmer Gertz who represented the family of a young man killed by police officer Richard Nuccio. Gertz took no part in Nuccio’s criminal case in which the officer was found guilty of second-degree murder.

Robert Welch, Inc. published a monthly magazine, American Opinion, which served as an outlet for the views of the conservative John Birch society. The magazine warned of a nationwide conspiracy of communist sympathizers to frame police officers. The magazine contained an article saying that Gertz had helped frame Nuccio. The article said Gertz was a communist.

The article contained several factual misstatements. Gertz did not participate in any way to frame Nuccio. Rather, he was not involved in the criminal case. He also was not a Communist.

Gertz sued for defamation. The court had to determine what standard to apply for private persons and so-called limited purpose public figures. Then, the court had to determine whether Elmer Gertz was a private person or some sort of public figure.

Robert Welch (above) founded the ultraconservative John Birch Society and was publisher of its monthly American Opinion magazine. His magazine published an article about Chicago attorney Elmer Gertz, leading to a libel case in which the Supreme Court defined categories of public figures. The magazine had said Gertz was part of a Communist plot to discredit police. Gertz won, with the U.S. Supreme Court saying he was a private individual and did not have to meet actual malice standards. Gertz eventually was awarded $400,000 in damages. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

The media defendant argued that the Times v. Sullivan standard should apply to any defamation plaintiff as long as the published statements related to a matter of public importance. Justice Brennan had taken this position in his plurality opinion in Rosenbloom v. Metromedia (1971).

The Court sided with Gertz on this question and found a difference between public figures and private persons.

The court noted two differences:

For these reasons, the court set up a different standard for private persons:

We hold that, so long as they do not impose liability without fault, the States may define for themselves the appropriate standard of liability for a publisher or broadcaster of defamatory falsehood injurious to a private individual.