Should men and women have equal rights under the law in the United States? It’s a simple question with a seemingly simple solution—a Constitutional amendment that guarantees that equal rights shall not be abridged on the basis of sex. But as the thorny history of the Equal Rights Amendment shows, getting the nation to agree on whether to adopt such an amendment has proven endlessly complex.

It has taken nearly a century of fighting to come close to passing and ratifying the amendment. And though its adoption seems tantalizingly close, it could still be prevented by a quagmire of legal issues. Here’s why the Equal Rights Amendment has never been adopted—and how it became a controversial issue during the height of the feminist revolution of the 1970s thanks to an enormously influential political activist named Phyllis Schlafly.

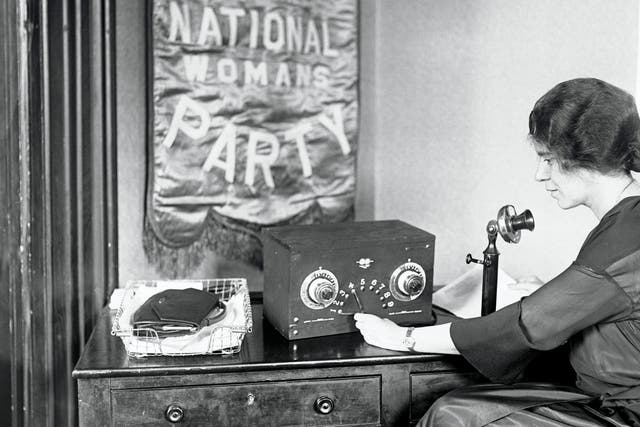

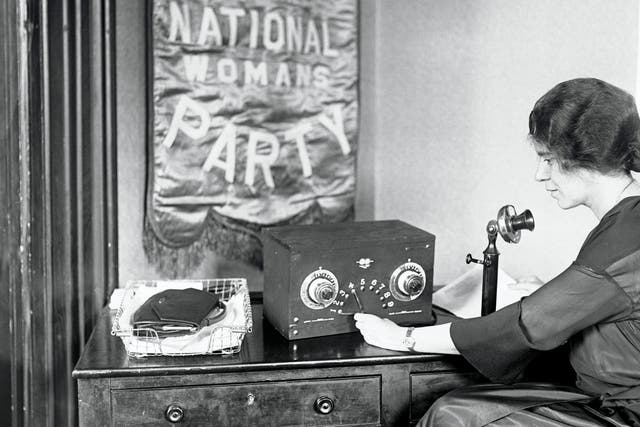

Though the amendment is a modern-day buzzword, its passage has been a goal of women’s rights advocates since even before the Nineteenth Amendment, which affirmed women’s right to vote, was passed in 1920. Suffragist Alice Paul proposed the first version of the amendment in 1923. She called it the Mott Amendment in honor of Lucretia Mott, one of the founding mothers of the American suffrage movement. Its wording was simple: “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

The wording may have been simple, but passing a constitutional amendment that guaranteed equal rights to women was anything but. Paul’s supporters proposed the amendment in every Congressional session between 1923 and the 1943, but it was never passed.

Then, in 1943, she proposed a new amendment that used wording similar to the verbiage used in the Fourteenth Amendment. “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex,” it read. Now known as the Alice Paul Amendment, it was introduced in every session of congress between 1943 and 1972.

In an effort to appease working-class opponents who feared the amendment would undo their years of attempts to protect women from discrimination under labor law, advocates of the amendment tried to add additional language that ensured the new amendment wouldn’t remove any existing protections specifically for women. But the core of the proposed amendment remained the same through the 1970s.

When second-wave feminism took hold in America, it ushered in a tidal wave of new support for the concept of constitutional equality between women and men. United States law increasingly called for equality of the sexes—the Civil Rights Act of 1964, for example, banned sex-based employment discrimination. But advocates wanted to take equality a step further, and their goal looked to be within reach.

By 1970, notes the Congressional Research Service, “Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Nixon were all on record as having endorsed an equal rights amendment.”

Suddenly, it seemed, the ERA was having its moment. The National Organization of Women vigorously promoted the amendment. Women organized huge demonstrations in its favor. It worked: In 1972, both houses of Congress passed the amendment. It sailed through the House, picking up a 93.4 percent majority, and won a 91.3 percent majority in the Senate. Now it was up to the states to ratify it. It would need three fourths of the 50 states—38 in all—to become law. And it would need to be ratified within seven years thanks to an agreement by both parties.

But as the proposed amendment finally broke through, a potent anti-ERA movement was brewing. In the fall of 1972, Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative political activist, began to organize a resistance to the amendment. Schlafly had first heard of the amendment a year earlier when she was asked to participate in a debate held by a conservative group in Connecticut. But the founder of the Eagle Forum group sensed a much bigger movement in the making.

“Sensing a burgeoning conservative backlash to the social and cultural changes of the 1960s, Schlafly rightly recognized that the rumbling discontentment of religious conservatives could grow into a powerful political movement,” writes historian Neil J. Young. “Schlafly intended to lead the charge.”

Schlafly formed a group called STOP ERA, or “Stop Taking Our Privileges, Equal Rights Amendment.” She warned women that if equal rights were enshrined in the Constitution, the heterosexual world order would collapse. Morality would fall by the wayside and women would be at risk of losing their femininity and the opportunities presented by marriage, Schlafly said.

“Suddenly, everywhere we are afflicted with aggressive females on television talk shows yapping about how mistreated American women are, suggesting that marriage has put us in some kind of “slavery,” that housework is menial and degrading, and—perish the thought—that women are discriminated against,” she said in a 1972 speech that she published in her newsletter, The Phyllis Schlafly Report.

If the amendment passed, she wrote, women would be forced to go to war, would lose their right to child support and alimony, and society would fall apart. “The women’s libbers are radicals who are waging a total assault on the family, on marriage, and on children,” she said.

Schlafly had an uncanny knack for bringing together women of diverse religious and social backgrounds—and making them seem more numerous than they really were. She insisted on equal airtime to rebut the amendment and taught her followers to remind everyone they spoke to that they represented a “silent majority.” She also painted feminists and ERA advocates as foreign, unappealing and dangerous.

“Everywhere, ERA opponents took care to present themselves as feminine rather than feminist,” writes historian Marjorie J. Spruill. They adopted pink as their trademark color, aggressively distributed anti-ERA literature, and charmed legislators with baked goods and earnest pleas to the gender status quo.

Schlafly single handedly turned the ERA from a widely accepted concept into a culture war…and spooked legislators in the process. Though the amendment had been ratified by 22 states in its first year, the pace of ratification slowed. Then, states that had ratified the amendment began dropping out. Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, and Kentucky, and South Dakota all voted to rescind their prior support of the amendment.

After a court battle, a federal district court ruled that Idaho could rescind its support and that the lack of support in the state should be recognized, indicating that if other legal challenges were brought, they would likely fall in favor of the states that rescinded their adoptions of the amendment.

In 1978, recognizing that the adoption pace was slow, legislators extended the ratification period to 1982. But the amendment only had the support of 35 states. The amendment wasn’t dead, though.

In 2017, Nevada ratified the ERA. In May 2018, Illinois followed. In 2020, Virginia became the final state to ratify the amendment. But it’s unclear what happens next. Since it expired decades ago, someone in Congress could give it a fresh start as a new bill, but it would then have to pass the House and the Senate and be re-ratified by all 38 states. If the additional states that ratified since 1982 are to be recognized, Congress would have to pass legislation that re-extends the deadline.

It’s unclear if the amendment could survive either attempt, or whether the ERA will eventually become law. Lawsuits would almost certainly accompany any concerted effort to make the ERA law by adopting the newer ratifications, and introducing the amendment anew risks having states that once supported the ERA fall off the “yes” list.

What is certain is that a simple sentence declaring equality of the sexes is, for now, a dream deferred. Its supporters have waited nearly a century for the amendment to pass, and even longer for equal rights. If the long afterlife of the Equal Rights Amendment is any indication, they’re willing to wait even longer.